The aim of this project is to help prevent knee injuries related to winter activities such as skiing and snowboarding. My research led to focusing on MCL injuries, which occur when the medial collateral ligament in the knee joint is stretched or torn due to inward force on the knee, commonly seen in skiers. I delved into the market for knee protection, and discovered that medical braces primarily aim to support ligaments, while sports knee pads concentrate on absorbing impacts. Using this knowledge, I set out to design a knee pad that could provide both support and impact protection. To achieve this, I developed a prototype knee pad using 3D air spacer fabric for cushioning and warmth. During my testing, I found the knee pad to be rather comfortable to wear, especially under ski lifts rides.

As many as 1 out of 3 competing athletes sustain injuries during the winter season. For the leisure skier on average 1,5 injuries happen every 1000th ski day. Although the number of general injuries while skiing, such as a fractured tibia, has fallen significantly over the past 30 years thanks to better designed bindings, damage to knees has increased, accounting for a third of recreational alpine skier injuries.

The aim of this project is to help prevent knee injuries related to winter activities such as skiing and snowboarding.

How is the knee built?

The knee is a hinge (bicondylar) joint, which consists of three main bones. On the upper side of the joint are the bones connected to the hip: the femur. The lower part of the knee joint is connected to the tibia and shinbone. The fifth bone in the knee is the kneecap. It is a small bone located in front of the joint, which moves with the knee when it is bent. The knee has four ligaments which are responsible for movement and keeping the knee together. Firstly, there are the ant cruciate ligament (ACL) and the post cru - ciate ligament (PCL). These two ligaments form a cross in the middle of the knee joint. The ACL is connected from the tibia, right beneath the kneecap, to the femur behind the knee joint. The PCL ligament connects the front of the femur to the back of the tibia. These two ligaments are the shortest ligaments in the knee. On the sides of the knee are the lat collateral ligament (LCL) and med collateral ligament (MCL). The collateral ligaments connect the femur to the shin-bone (LCL) and the femur to the tibia (MCL). [15 [17] [16] The final component of the knee is the meniscus. The meniscus is two crescent shaped discs of cartilage that lie in between the femur and the tibia. They absorb and distribute the shock from jumping up and down for example.

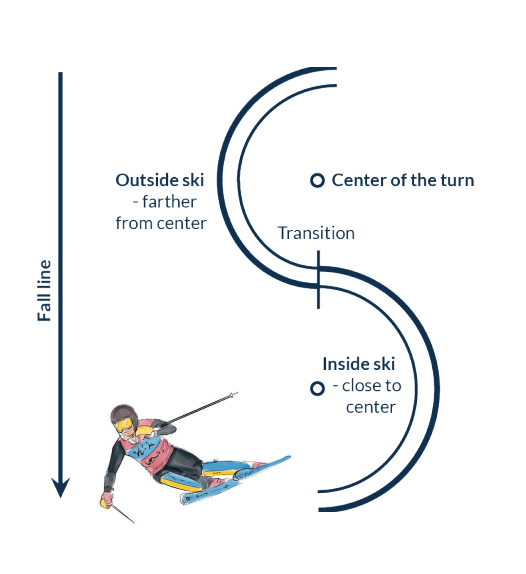

How an injury can occur Valgus–external rotation:

The valgus-external rotation position is a type of knee position that can occur while skiing. It involves the knee joint moving inward (valgus) and rotating outward (external rotation) at the same time. This position places significant stress on the medial collateral ligament (MCL) of the knee, making it vulnerable to injury. The valgus-external rotation position can happen when a skier loses their balance, or is attempting to turn sharply, causing their skis to carve into the snow and altering their direction. [14] [3], [4], [7] [17] Other common causes for injuries are: Phantom foot: This is when your hip lays below your knees. Making you unbalanced which can result in an accident. Boot-induced Mechanism: Commonly occurs when lading from a ski jump. The ski tail contacts the snow first.

CONCEPT DEVELOPMENT

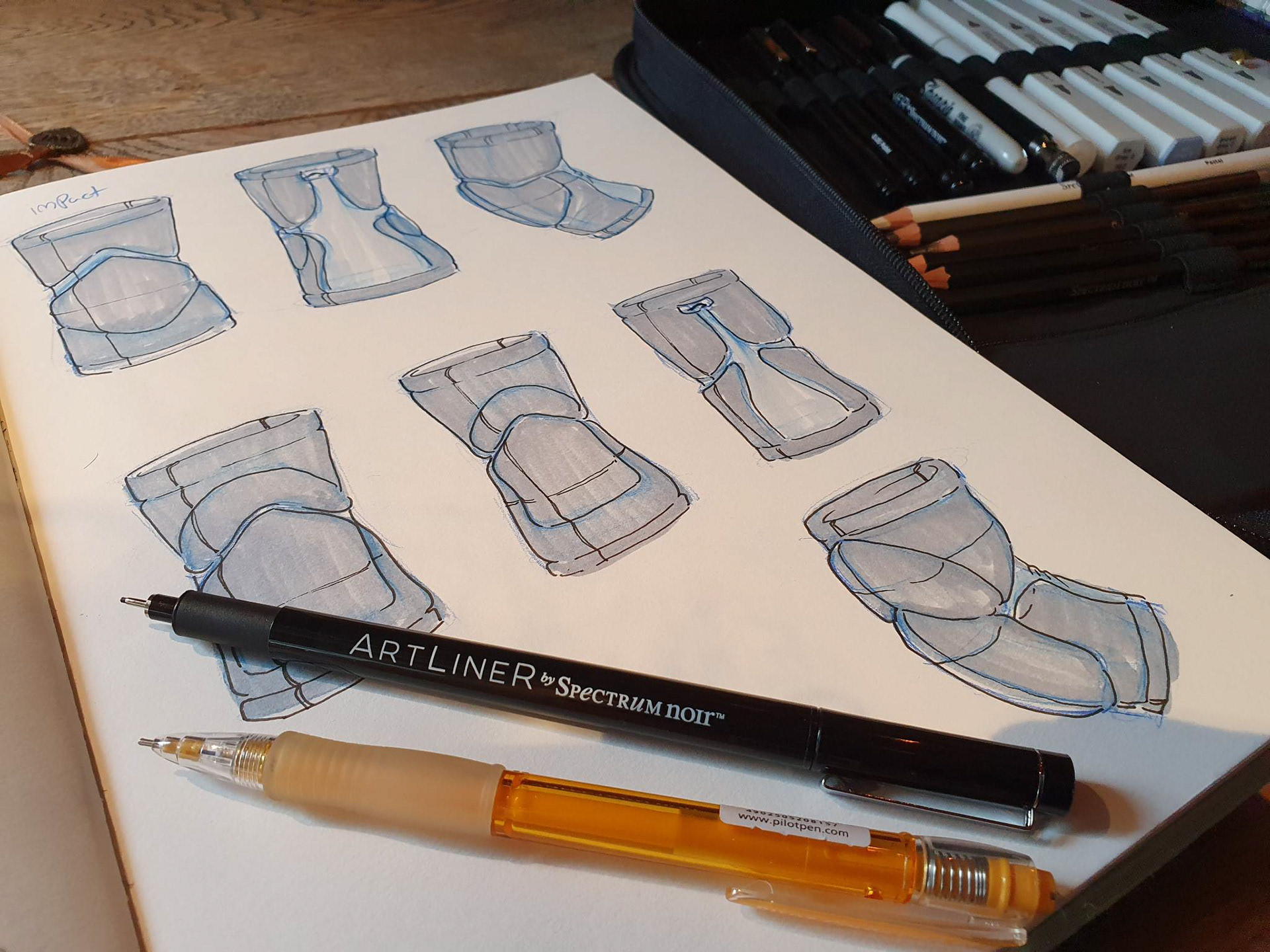

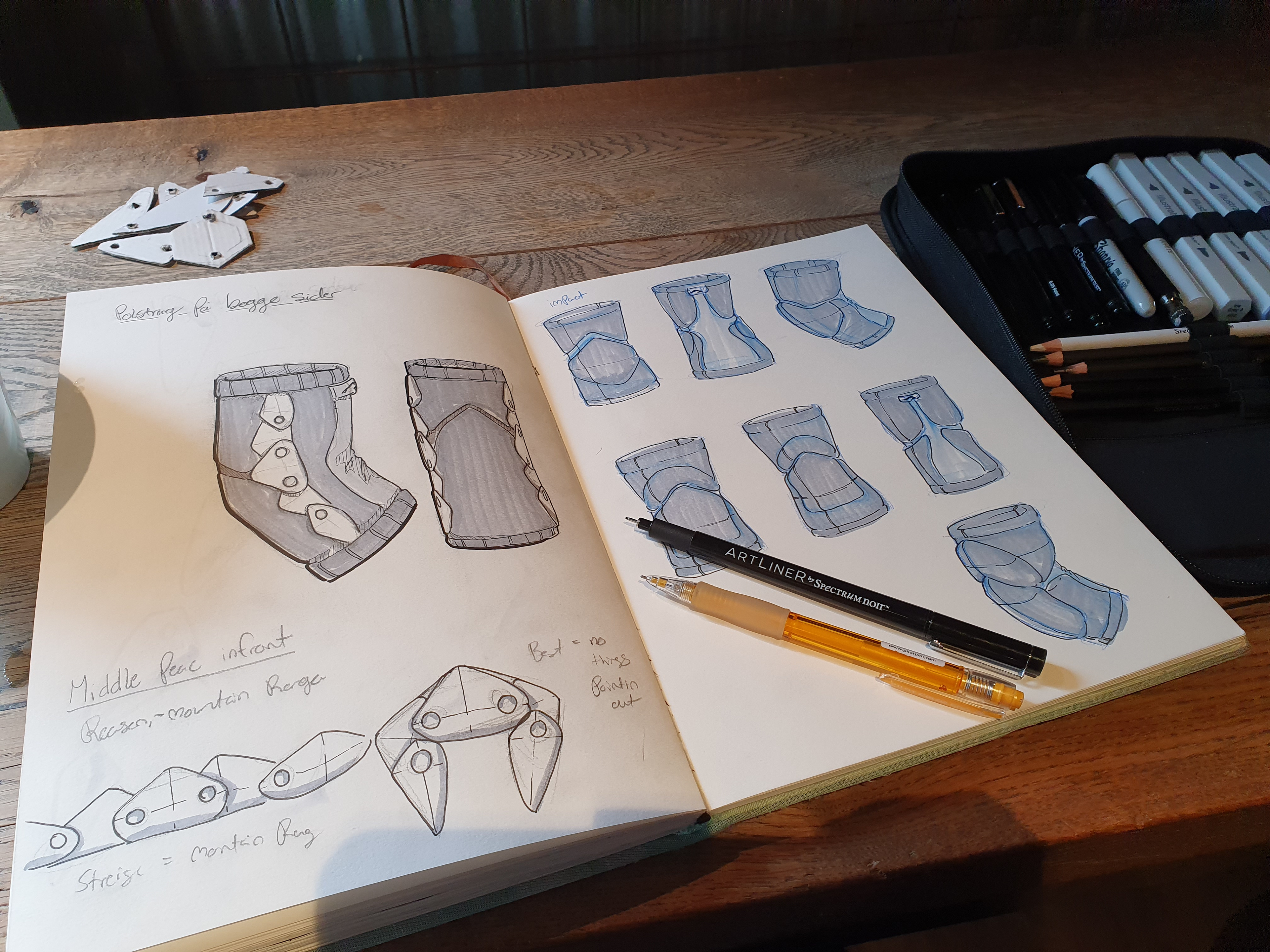

Playing with shapes

During my process I felt, I needed to take a step back from ideation, and look more at the main shape and structure of the product. Now that I started to get a better idea of what qualities were required, I could test out if there was any room to push and pull the shape. The shape would still have to be quite confined to the shape of the knee.

Front side:

As I examined the front of the knee pad, I found myself grappling with a crucial design decision. Specifically, I was uncertain whether to prioritize a padded knee pad or one that utilized elastic bands. This was a critical choice as it would significantly impact the overall comfort and fit of the knee pad. I took some time to weigh the pros and cons of each option, carefully considering factors such as the level of protection offered, the range of motion it permitted, and the ease of use. Ultimately, I decided that the best approach would be to experiment with both styles and determine which one would be the most effective in meeting the design goals.

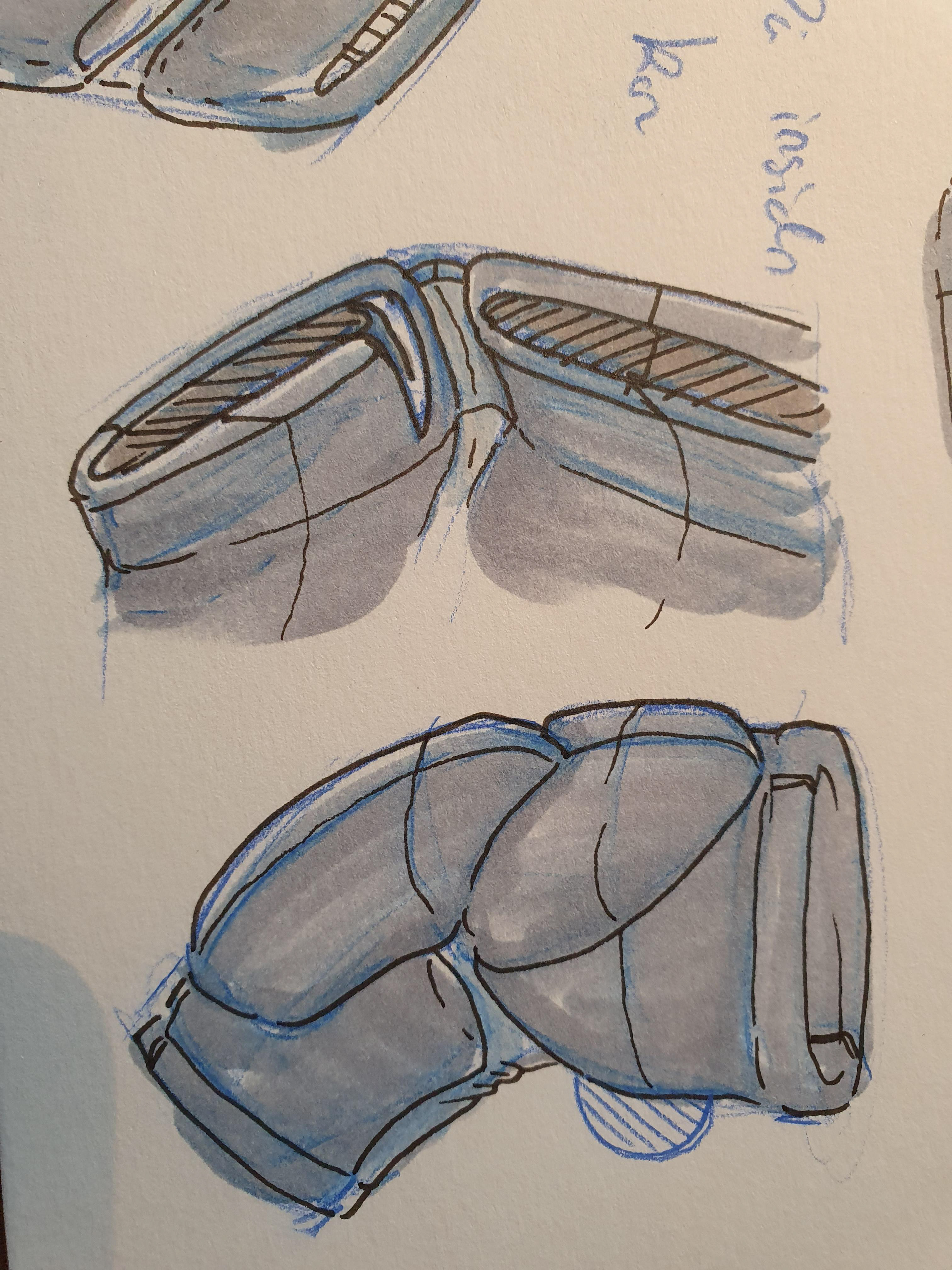

Back side:

When I worked on the back side of the knee pad, I kept the medical knee braces in mind, as inspiration. By doing this, I was able to glean insights into the most effective ways to structure the back side of the knee pad, ensuring that it would be both functional and comfortable to wear. Here I also sketched out where I should prioritize more stretchy material.

Looking at different ways of keeping the knee pad in place

Next I needed to figure out what kind of mechanisms, I could use in my product to keep it in place on the knee. To do this I first drew out what the most common mechanisms were. During this process I had questions such as ‘should the product be able to fully open or just be a tube?’ and ‘is there an unconventional method that could be more fitting?’ in mind.

Idea sketshes and paper muckups

3D print tests

Simple mockups